Challenging the WHO’s Stance on Vaping: A Critical Perspective

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recently reiterated its stance against recommending vaping as an alternative to smoking, citing the complexity and unknown long-term effects of e-cigarettes. This position starkly contrasts with the NHS’s advice, which recognises e-cigarettes as a significantly less harmful option for those seeking to quit smoking.

The WHO’s Position and its Implications

The WHO’s newly published guidelines state that “e-cigarettes are beyond the scope of this guideline because the potential benefits and harms of using these products are complex and are addressed in a separate body of literature.” They also add that vapes “may” be recommended as a smoking cessation aid “in the future as evidence accumulates.” Instead, the WHO recommends traditional cessation methods such as behavioural support, nicotine replacement therapies, and smartphone apps.

While it is crucial to prioritise public health, it is equally important to question and critically evaluate such recommendations, especially when they contradict established national guidelines. The NHS, for example, asserts that e-cigarettes are far less harmful than smoking and can significantly aid in smoking cessation efforts. Public Health England, which the UK Health Security Agency has since replaced, published an expert independent review in 2015 concluding that e-cigarettes are around 95% less harmful than cigarettes. This divergence in recommendations highlights the ongoing debate and confusion surrounding e-cigarettes.

Historical Inaccuracies and Overestimations by the WHO

It is not the first time WHO’s recommendations have sparked controversy or been later proven inaccurate. Let’s take a moment to reflect on some notable historical inaccuracies and overestimations by the WHO:

-

- Swine Flu Pandemic (2009): The WHO declared H1N1 a pandemic, causing widespread panic and substantial financial expenditures on vaccines and antiviral drugs. The actual impact was comparable to a typical flu season, leading to criticisms of overreaction and unnecessary alarm. A report from the Council of Europe accused the WHO of causing a “false pandemic” and inducing a panic that resulted in billions spent on ineffective vaccines and medications (BBC ).

-

- Ebola Response (2014): The WHO was criticised for its slow response during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Internal documents and reviews later revealed that the organisation had downplayed the severity of the epidemic in its early stages, which hindered the initial containment efforts and contributed to the rapid spread of the virus. The delay in declaring an international public health emergency was seen as a major misstep that exacerbated the crisis (The Guardian).

-

- HIV/AIDS Predictions: In the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the WHO predicted that the virus would rapidly spread among the heterosexual population in the West. While HIV/AIDS did become a significant global health issue, the pattern of transmission was more complex than initially projected, with the highest rates occurring in sub-Saharan Africa. This misjudgement highlighted the challenges in predicting disease spread and the importance of targeted interventions based on accurate epidemiological data.

-

- Climate Change Predictions: In alignment with other organisations, the WHO has supported various climate change predictions that have not come to pass. For instance, predictions of Arctic ice disappearing by 2013 and other dramatic climate changes have not occurred as predicted, leading to criticism of alarmism and inaccuracies in climate modelling. These exaggerated predictions sometimes undermine public trust in legitimate environmental concerns (Grunge).

-

- First Earth Day Predictions (1970): Though not directly by the WHO, influential ecological scientists around the time of the first Earth Day made dire predictions about population growth, food scarcity, and pollution, many of which were overly pessimistic. Predictions such as widespread starvation due to overpopulation did not materialise thanks to advancements in agricultural technology, known as the Green Revolution. Similarly, dire predictions about pollution causing urban dwellers to wear gas masks within a decade did not pass, partly due to environmental regulations and technological advancements (Smithsonian Magazine).

The Current Debate on Vaping

The ongoing debate about vaping reflects a broader issue within public health: the challenge of balancing potential risks with proven benefits. While the long-term effects of vaping are still being studied, there is substantial evidence that e-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes. The NHS and other health bodies emphasise that vaping exposes users to fewer toxins at lower levels than smoking.

E-cigarettes do not contain tobacco, nor do they produce tar or carbon monoxide, two of the most harmful components of cigarette smoke. Instead, they deliver nicotine through a vapour, which significantly reduces exposure to harmful substances. Public Health England’s review concluded that e-cigarettes are around 95% less harmful than smoking, and the Royal College of Physicians has also endorsed vaping as a viable harm-reduction tool.

However, it is important to acknowledge that vaping is not without risks. Studies have shown that e-cigarettes contain harmful toxins, and their long-term effects are still unknown. Concerns have been raised about the potential for vaping to cause heart problems, lung disease, dental issues, and even cancer. The number of adverse side effects linked to vaping reported to UK regulators has eclipsed 1,000, with five of them fatal. These reports range from headaches to strokes, highlighting the need for ongoing monitoring and research.

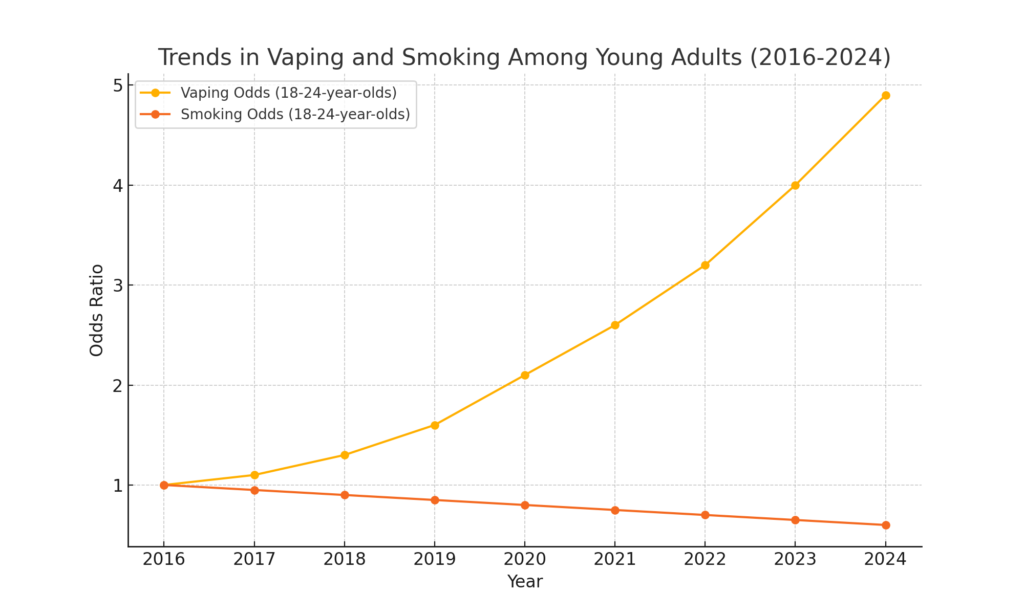

The Rise of Vaping Among Youth

One of the most pressing concerns is the rise in vaping among young people. Figures show that the proportion of kids using e-cigarettes has exploded amid the decline of traditional smoking, with more than a third of 16 to 18-year-olds now regularly inhaling them. This surge has sparked fears about the long-term health implications for this generation.

Campaigners have blamed manufacturers’ predatory marketing tactics for this trend, claiming they intentionally lure kids with colourful packaging and child-friendly flavours like bubble-gum and cotton candy. In response, some governments have implemented stricter regulations. For instance, Australia now requires a prescription to purchase e-cigarettes, and New Zealand has set restrictions on vape shop locations and requires all vapes to have removable batteries.

Conclusion

The WHO’s cautious stance on vaping reflects the complexity of balancing potential risks with proven benefits. However, their historical inaccuracies and overestimations highlight the importance of critically evaluating their recommendations. E-cigarettes represent a significant harm reduction tool that has already helped many smokers quit. As evidence accumulates, public health policies must remain flexible and grounded in current scientific data.

At Our Vape Advocacy, we remain committed to advocating for informed, balanced, evidence-based policies that genuinely support smokers’ quitting journey. Let’s ensure that public health decisions are grounded in comprehensive, up-to-date evidence and consider the full scope of potential benefits and harms.